Here we go again? Twenty years ago, the question being asked was “can you replace a teacher with a computer?” A case of déjà vu? There is a phrase in Hungarian that translated roughly means “there is nothing new in the world, only those things that we have forgotten”.

The standard answer 20 years ago, was “any teacher who can be replaced by a computer should be replaced by a computer”. Is it different this time? For a start, developments in “big data”, “artificial intelligence” and “machine learning” are impacting on other professional disciplines. In medicine, diagnostic systems can outperform skilled clinicians. The practise of law is being impacted by these technologies. We can find examples in architecture, accounting and many other disciplines. There are many studies suggesting that 40-60% of today’s jobs will be eliminated or seriously transformed in the next 20 years by advances across the technology spectrum. Can education claim sufficient uniqueness that teaching alone will not be impacted by robotics and AI?

The problem about the above paragraph and many like it, is that it addresses the wrong question. Try this instead: “how can the education system, its institutions and professionals embrace, appropriately, advances in technology to improve access to and the experience of learning for professionals and students alike?”

Do you believe that the education system that we have is the best that there could be? Would an injection of more money, on its own, eliminate all significant challenges? I’d be happy to debate with anybody who believes that both the above questions can be answered yes.

For a start, technology has played a significant part in special needs education in lowering the barriers. We still have serious educational inequalities to address. Teacher stress leading to retention problems, difficulties in finding enough Heads. I could go on, but you know them better than I do.

For as long as I have been engaged with educational technologies, there has been a constant background debate about how to make education a researched-based profession. Too much education research is too small to have a real impact on policy and practise, be it at institutional or classroom level.

I would argue that the current round of technology advances provides the platform for the realisation of the teacher as an action researcher at scale. Links between education researchers and practitioners could at the system level using big data, AI and machine learning and low cost computing help create a culture of education research led by the needs of teachers. In my experience, schools do not suffer from a lack of creativity or innovation. The problem that I have seen is that innovations do not spread across the system. Imagine a health system where each hospital defined its own treatment and drug regimes. Health has its own problems, but there is a culture of spreading practise systemically. I can still use examples from the 1990s about practise in schools that I observed such as virtual reality in a primary school, modern foreign languages between children in classes in different countries and people think I’m talking about the future.

Now let’s look at the school level. Here I would argue is that schools have become masters of adapting to change imposed on them, often framed in the language of earned autonomy, guided localism. You are free to do what we tell you! My own feeling is that people do not resist change, they resist being changed.

I would argue that if schools do not embrace these advances they are not preparing young people for adult life and work in a world where these technologies will be pervasive. However, the obvious push back is that the computer that a 5-year-old uses will be nothing like the ones they will use when they are adults, so how can schools deliver without massive injections of resources?

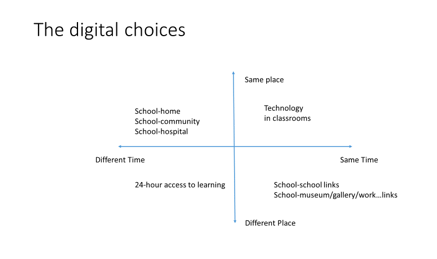

Consider the diagram below:

Start by thinking about problems and opportunities you have, at classroom level or at institutional level. Back in the 1990s I evaluated a small project where a number of children with serious health problems were given technology that enabled them to stay involved with their school, their friends when in hospital or at home. When one child was in remission they were able to be reintroduced back to school without having experienced significant disruption to their education while away. Think about how you might enhance the education in your school by external links. In the 1990s I was involved in a school project where we had an “artist in non-residence”. An art teacher working in a school classroom had access to a professional artist who contributed to a school art project from his studio miles away. In a deprived community, another school opened at evenings and weekends to train parents and grandparents in how to use computers, true community schooling.

These examples all started from ideas generated from practitioners having real problems that they wanted to see if computers could help. The lesson 20 years ago, and now is the same. The Learning horse pulls the technology cart, not the other way around.

In stable times, our values and purposes can be implicit. In changing and turbulent times, we will get nowhere if we are not confident in our purpose and values.

So, what are the purposes of education? What are our values, as society, teachers or parents? These are old questions. We have new tools of incredible potential, but it is potential only.

My advice is this. Don’t be afraid of AI, machine learning, robots and big data. On the other hand, do not be complacent about change. The work teachers do will be different. How schools operate will change. The issue is whether we manage change well, or badly.

So, what would be my hopes for the next 10 years?

- We think about building a model of change management for education at the system and institutional level that involves and engages the professionals throughout the change process

- We build a system for diffusing innovations that work across all schools. Research in education should, at least in part, be driven by practitioners needs and assessed by their outcomes.

- We take the ideas of “schools without walls” seriously and look how links to other institutions can enrich the experience for teachers and pupils alike.

- We build new models for the development of both curriculum and assessment that consider technology advances and how teacher satisfaction and skills are part of the process not a bolt on or afterthought. I am reminded of Seymour Papert: “don’t teach children about computers, use computers to teach them about the world”. Please remember that computers are in that world.

- We need an education system at every level is confident about its purpose and values. We are preparing children for a world which we do not understand. Alec Reed, founder of REED Group put it to me well 20 years ago, He described the culture change in comparison to another rite of passage. He envisaged success as a world where students on leaving school put on their L plates to say “I am a learner” rather than take them off because they passed or failed.

At the end of the day, throwing technology at an ill-defined problem doesn’t help. If the dialogue goes like this “the answer is X, what’s the problem”, you know we are the next in a long line of “modems in cupboards” initiatives.

I used to say that the biggest policy problem was the flawed belief was

NEW TEACHER = OLD TEACHER + IT

Add to that OLD WORLD (Teacher) NEW WORLD (Robot +AI).

The College of Teaching is a welcome development for me. Its aspirations fit my beliefs about what education needs to be, at the forefront of building the adults and workforce of the next generations.

Have a fun and productive 2017.

Chris is an independent Consultant specialising in Innovation and futures thinking. He has a 30 year background in IT and 25 of IT in Education. He is also a Patron of NACE, The National Association of Able Children in Education.